Barrow Cemetery and Settlement

2019 Data Structure Report.

In 2019 TARRADALE THROUGH TIME examined the site of a large barrow cemetery to the west of Tarradale House. In the 1990s Professor Barri Jones excavated part of a nearby large ditched enclosure site which he initially thought may have been a Roman fortification. However it clearly is not Roman and the evidence he found suggested a multi-period occupation from Mesolithic through to early medieval. He did not investigate or comment on the potential relationship between this enclosed settlement and the nearby barrow cemetery.

The University of Aberdeen (on behalf of NOSAS) undertook geophysical survey of the ploughed out area of Tarradale barrow cemetery. Results suggested a range of surviving features below the plough soil but also some discrepancy with the pattern of crop marks seen on aerial photographs. The barrow cemetery is one of the largest in Scotland and appears to have been used for a considerable period of time as the barrows within it (seen on aerial photographs) comprise large circular barrows, smaller circular barrows and square barrows. The 2019 excavation examined part of the barrow cemetery that has now been ploughed out (with potential features apparent on aerial photographs) and a small rough area that appears never to have been ploughed that may still contain original barrows though there is some suggestion of disturbance of that site for extracting sand and gravel.

Aerial by Andy Hickie with barrow plan by Juliette Mitchell of Aberdeen University superimposed.

See also the blog post.

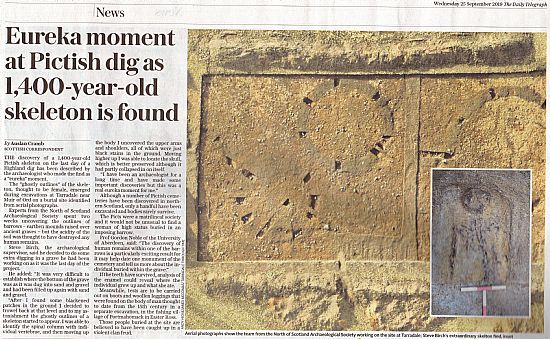

Once stripped, the ditches of the barrows and enclosures revealed in 3 large trenches was quite spectacular:

The TARRADALE THROUGH TIME excavation in September 2019 was a major research excavation to find out to what extent the features on the aerial photographs survive underground. We opened three large trenches (totalling almost half an acre) carefully chosen to explore the different patterns and sizes of the barrows. It soon became clear that the cemetery had been built on a vast scale. Trench 1, on the highest part of the site, revealed four large ditched barrows cut into the very stony soil. While aerial photographs had suggested some loss of barrow features in this area owing to plough damage and natural soil erosion downhill, we found the ditches and the bottom of the grave cuts to be relatively well preserved and, but no human remains or grave furniture survived.

In trenches 2a and 2b we investigated a very different soil type (a sandy substrate) with a very different pattern of barrows. Here we found a large segmented ring ditch some 30m in diameter, 1m-1.5m deep, and steep-sided, and while there was no sign of a grave within it, the presence of two fragments of beaker pottery (one from the ditch, plus an earlier topsoil find) hints at a Bronze Age date for this barrow. If this is correct, we believe that this earlier feature was still a prominent landmark in the landscape around 2000 years later when a large Pictish square barrow (17m across with causewayed corners and on stylistic grounds presumed to be Pictish) was laid out nearby (revealed in trench 2b).

The large square barrow in trench 2b had been more than quadrupled in size when it was surrounded by a second square enclosure of truly impressive proportions measuring 40m across, with ditches up to 7m wide and 2m deep. Whether this was constructed contemporaneously with the inner square or as a later enlargement and aggrandisement is not known, but the resulting double-ditched square barrow enclosure is the largest of its kind known in Scotland. No burial was found but it was abundantly clear that this prominent feature, still shown on an estate map of 1788, had been levelled in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. If it was a burial mound (though a shrine or some kind of funerary meeting place are other interesting possibilities) it hints at an occupant of the highest, possibly royal, social status.

Trench 3 was a massive undertaking, opening an area 40m long and up to 25m wide, and as the hundreds of tonnes of soil were scraped back, an amazing array of ditches and pits emerged. A round barrow 7m in diameter (containing a clear central grave cut) lay a short distance from a larger (17m-wide) round barrow, with another large example beyond. Close by, two neatly laid-out square barrows, c.8m wide with causewayed corners, were accompanied by a larger diamond-shaped, barrow 13m across. Sections across the barrow ditches revealed them to be only 1-2m wide and fairly shallow, and both within and without the barrows there were numerous pits and areas of burnt soil, as well as several unenclosed graves scattered between the monuments.

An account of the 3 week excavation as it unfolded can read in our blog posts. On the very last day we had a significant find, read more in the BBC Online story.

Survival of graves

Despite the presence of these graves, the acidic local soil meant that any human remains that they might have contained have not survived. We decided to investigate two graves more closely, the first being an unenclosed cut lying between two square barrows. Here too, no human bone was found, but the outline of a log coffin was preserved as a dark stain in the soil, confirming that a burial had once been present. The second grave lay within but towards the side of the diamond-shaped barrow. It was initially difficult to discern during excavation if the bottom of this grave had been reached as the graves are difficult to define as a result of being cut into fairly homogeneous light-coloured sands and gravels and backfilled with the same material. However, we could see some intriguing blackened patches emerging, and – in true archaeological tradition – on the final day of the 2019 excavation, inspired trowel work by Steve Birch, the director of the excavation, revealed the shadowy outline of a human skeleton.

No complete bony structures had survived – the shape was purely a chemical deposit from the complete deterioration of the skeleton – but it was remarkably detailed, with each vertebra of the spine and the shape of the upper arms and shoulders, legs, and feet visible. Interestingly, the lower limbs seem to have been bound together before burial, and the whole individual was surrounded by the faint outline of a log coffin. The skull had survived slightly better, though it had collapsed in on itself. The skull was lifted for further investigation and it is hoped that if any teeth survive in the sand filling the cranium, we may be able to carry out isotope analysis to learn more about this individual’s life.

The emergence of monumental cemeteries like Tarradale is seen as an important transition in the visibility of the dead in the archaeological record. The creation of larger barrows may be linked with the emergence of elites and kingship, and the aggrandisement of existing grave mounds with the increasing status of the deceased’s descendants. Yet this kind of monumentality begins to disappear in the region from the 7th century onwards, possibly owing to the evolution of overkingship based in southern Pictland and the growing influence of Christianity favouring simpler burials close to churches. The TARRADALE THROUGH TIME project has dramatically shown that, elusive though the Picts may be there is still considerable evidence beneath the plough soil of powerful elites.